The single best machine to measure trust is a human being. We haven’t figured out a metric that works better than our own sort of, like, ‘There’s something fishy about you’.

– Simon Sinek

The dehumanizing I referenced yesterday at the conclusion of my blog is a commonplace in modern society. Its most recognizable manifestation is heard in the common complaint that we are, as individuals, too often treated as numbers or that the system (whatever system you might choose as an example) doesn’t deal with us personally. In the latter instance, all you need recall is the last time you phoned any organization and were treated to a variety of voice prompts that may have, if you persisted long enough, led finally to a live responder. Increasingly, though, as the technology advances, it is entirely possible to conduct your business without ever actually conversing with anyone. I suspect we don’t take much time thinking about the pros and cons of such a system, other than to complain, perhaps, about how annoying it is. But then, why should we? Irritating sometimes? Yes. Reason for a crusade against automation? Hardly.

I mention this, however, as an example of how we have come to accept technology as a complement to virtually every activity we undertake as human beings. I received a Fitbit for Christmas so now I can monitor my physical activity. I can know how many steps I walked, how “active” I was (beyond simply walking), check my sleep patterns, link to other apps, and monitor food intake and calories consumed. I’m sure it does other things of which I am unaware.

Some thirty-five years or so ago, I remember having moved in the middle of a strike by some union or other from the phone company. I ended up without a phone for the better part of six months. If anyone wanted to contact me, or me them, a real effort had to be made. I actually enjoyed the sense of freedom that seemed to be a consequence of being so “offline” if you will.

These days, I am very familiar with cellphone anxiety (if it isn’t a recognized condition, give it a while). It can strike me when I’ve gone out, regardless of the reason, and forgotten my phone at home. I’ve seen it at work in others on any number of occasions. If anxiety is related in any way to frequency of use, then young people are in greatest danger of infection. Who has not been privy to a room full of teens and twenties where virtually everyone is, in some way, attached to his/her phone, even if involved in conversation or some other activity?

I no longer need to use a key in my car; if I want to watch a show, I have any number of avenues that will allow me to watch it whenever I feel like it; if I’m traveling, a physical map – if I even have one – is there exclusively as a back-up to my GPS; I don’t have to remember an appointment – I simply enter it in my phone and make sure I set an alert. Add anything that occurs to you – by way of technological innovation – that has significantly changed the way you live your life.

While much discussion could be had over the positive or negative elements of all, or any one, of these changes, whatever they might be, I am more interested in what I believe is the “meta-message” (to coin a term) that arises from the growing predominance of technological advance in public consciousness over the last fifty years or so. While naysayers exist, the dominant conclusion that is trumpeted again and again – whether through news outlets, corporate entities, governments, individuals or some other means – is that technology is GOOD.

And I’m not suggesting for a moment that it is bad. What concerns me, however, is the application of that meta-message, “technology is good”, to areas where it should be viewed somewhat more critically. From the outset, I have wanted to use this blog to argue for the realization/recognition that few things are simple. By making so many of the commonplace features of daily activity “simple”, “simple” has a tendency to become a value in itself. Technology, in its application, aims to simplify tasks, to lessen the need for human activity or thought. No need to remember a phone number: put it in your phone. Televisions without a remote control? I’m not sure if you even CAN change a channel on a TV these days without one.

If technology can provide increasingly successful simplification of onerous tasks, it becomes all the more likely that we, as a society, would accept the idea that technology can be employed to “improve” pretty much anything. Our acceptance of that notion is all the more understandable when just such a claim is made by the “experts”, regardless of the field in which they are working. The result of this process is the “techno-faith” I’ve tried to outline in earlier blogs.

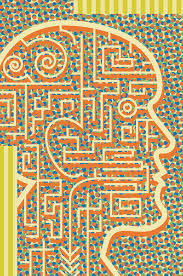

And this is where “techno-faith” and education collide. When we use our cellphones, we rarely stop to ponder – if we ever do – how they work. They work and such is the nature of modernity. If we think about it for even a moment, though, I’m sure we can summon at least a smidgen of awe over what it is we are able to do. From virtually anywhere in the world, I can be in contact with anyone else who has a phone on him/her (providing I have the number) no matter where he/she is in the world. The people who design such things understand how it all works, but we don’t have to bother ourselves with such matters.

When it is an object such as a phone that we are concerned with, our faith in the technologists and the developed technology seems justified. Today’s phones are better than those from even 2 or 3 years ago (maybe even 6 months ago). But what happens in schools if an idea takes root that we can treat children in the same manner as any other “thing” that we would hope to make “better”? In the peculiar doublethink of modern educational theory, we talk about embracing diversity even as we strive to develop “tools” (the system’s word, not mine) that – should the technology of delivery/instruction be perfected – will lead to near-uniform “outcomes.”

The “experts” in education want you to have the same faith in the system they say they are building (fixing, tweaking, creating, modifying, reforming – choose your participle) that we are asked to have in Apple as it releases its latest iPhone. In this instance, Apple alone has credibility.