The whole modern world has divided itself into Conservatives and Progressives. The business of Progressives is to go on making mistakes. The business of the Conservatives is to prevent the mistakes from being corrected.

– G.K. Chesterton (1874-1936)

If you’ve been following the fallout from Donald Trump’s election, one designation has been increasingly prominent in the analysis: “progressive.”

Perhaps you have long been familiar with this term (in the sense I am using it) but I first encountered it a couple of years ago. Progressives commonly define who and what society should champion, defend, promote, even believe. They commonly hold that they are beyond meaningful challenge by virtue of their positions’ intrinsic righteousness and, in fact, they are seldom challenged (at least until recently) because they tend to be on the “politically correct” side of many issues we commonly encounter in the press and other public forums.

And the thing is, I commonly agree with their core assertions: climate change is real; LGBT rights are human rights; Islam is a religion, not a terrorist organization; women, for all the strides they have made, are still subject to misogyny, double standards and sexism; etc.

Unfortunately, for all of their good intentions, the progressives or, perhaps, the “liberal left” are victims of their own conviction and certainty. Any number of analysts have pointed to the tunnel vision of those who felt that Donald Trump was unelectable. While I share their despair at Trump’s election, I was never convinced that he couldn’t win. I fear those who were entirely disbelieving haven’t paid enough attention to history.

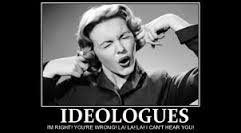

And while we are fellow travelers in so many ways, the progressives and I diverge at a fundamental level. Progressives are too often, to my way of thinking, ideologues. As an idealist myself, I think it is important to recognize that someone can share many of the ideals proclaimed by progressives without falling into the ideologue trap, a trap that prevents the ideologue from carefully considering a reality that is, perhaps, staring you in the face.

The ideologue claims a position on an issue, commonly social/political, that is essentially unassailable, a secular version of fundamentalist religion you might say. Watching mainstream media outlets, particularly CNN, on election night in America was fascinating. I had been watching CNN in the weeks and months leading up to the election far more than I ever had.

And make no mistake, the preference for and expectation of a Clinton victory was predominant. However much the various anchors tried for balance, each and every segment involved those who were defending Trump being exactly and exclusively that: defenders. And to be clear, I get it. Everything about Trump, his campaign, his rallies trended toward the repulsive – for me! At the same time, attention needed to be paid to the reality that a huge segment of the population found Trump to be preferable. The New York Times – giving credit where credit is due – has gone so far as to admit that they need to get out of the newsroom more and talk to people on the ground.

Progressive ideologues play easily into the hands of the so-called alt-right. The progressives’ ideological righteousness and the accompanying dismissal of any point-of-view that diverges from theirs contribute to the radicalization of what might otherwise be simply different opinions.

Listening for and seeking to grasp differences, however, have become casualties of our preference for being pseudo-informed. When the public forum is dominated by 140-character tweets, headlines and sound-bites, the effect is insidious. Increasingly, few have time for a lengthy consideration of anything. Slogans take the place of arguments, positions become hardened and unassailable, and extremes become the norm.

Canada, so far, has avoided this trap but we cannot be complacent. Conservative leadership candidate, Kellie Leitch – she of the “Canadian values test “ who wants to eliminate the CBC – has her followers and dismissing those who are sympathetic to the positions she brings forward will not convince them to give either consideration further thought. If we don’t learn to listen to one another, we risk outcomes a great many prefer not to imagine.